Peter Ramsden is a Pole Manager for the EU URBACT programme helping cities to exchange and learn from good practices, as well as managing director of the micro-consultancy Freiss ltd, also focusing on social innovation and local development. He has worked in the European Commission, in the Regional Development Agency movement, in the public and private sectors and various think tanks. He co-wrote the EU Guide to Social Innovation and the guidance for Community-Led Local Development CLLD in Europe and was the lead author of the OECD paper “Innovative Financing and Delivery Mechanisms for Getting the Unemployed into Work” .

Peter Ramsden is a Pole Manager for the EU URBACT programme helping cities to exchange and learn from good practices, as well as managing director of the micro-consultancy Freiss ltd, also focusing on social innovation and local development. He has worked in the European Commission, in the Regional Development Agency movement, in the public and private sectors and various think tanks. He co-wrote the EU Guide to Social Innovation and the guidance for Community-Led Local Development CLLD in Europe and was the lead author of the OECD paper “Innovative Financing and Delivery Mechanisms for Getting the Unemployed into Work” .

Peter Ramsden gave an overview on the process and scope of social innovation. He pointed out the essential role of the public sector and emphasised the need to involve all the stakeholders – above all the target group – and to focus on results. Part of his presentation also focused on the chances of innovative financing.

Peter Ramsden started his presentation with a photo of the first job center or „Labour Exchange“ set up by Winston Churchill in 1909. Since then, much has changed: flexibility increases at the expense of security, the “necessity entrepreneur” is by now a common phenomenon and some make ends meet only by patching a portfolio of different jobs and projects, especially in the creative sector, and also many university graduates are unemployed.

However, there are certain groups who are disproportionally hit by these labour market problems: Migrants, lone parents, especially single mothers, young people and the disabled are struggling especially hard to gain a foothold in the labour market. Social innovation is a method to tackle these challenges to be applied now. For as it is now “the problems are innovating faster than the solutions“, as Peter Ramsden put it, who wishes we would return to the stream of ambition and optimism we had in the post war 1940s to 1960s when the welfare state was invented. It now has to be re-invented and social innovation is a part of this.

What is social innovation?

Social innovations are new ideas (products, services and models) that simultaneously meet social needs (more effectively than alternatives) and create new social relationships and collaborations.

However, social innovations also need to be “innovations that are not only good for society but also enhance society’s capacity to act“ – which is something, the labour market policy of the past has been failing at. Hence, the challenge now lies in empowering the users of social services. Addressing the audience, he emphasized that “all of you are social innovators”. Innovation is not just a thing for google and facebook. It can be a deliberate thing to do when people decide to innovate.

Social entrepreneurship plays an important role as social enterprises can be more nimble than the public sector and make change happen. Still, social innovation is not all about social entrepreneurship. It is the public sector that “holds the ring” and enables social innovation by creating the space in which it can happen.

The role of the Public Sector

What is needed therefore is a dynamic transformation in how the Public Sector works. Instead of merely managing human resources, public authorities should be shifting to building capacity for innovation. What is needed is a shift from random innovation to a conscious and systematic approach to public sector renewal. Along the whole chain of governance, from the EU level to municipalities, authorities need to understand what social innovation is and how they can contribute to it. Instead of running tasks and projects they should be conductors “orchestrating processes” of co-creation as they are the ones who can promote social innovation in a systematic manner across and beyond the public sector.

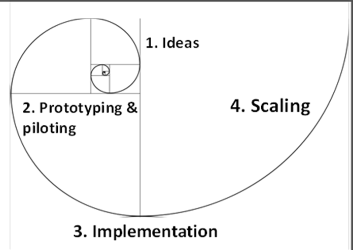

Peter Ramsden led the audience through the different stages of creating and scaling innovation: After the idea creation in the prototyping phase, it is important to adopt a design thinking process and adjust an idea until it really works. If necessary, things have to be tried out 20 times before they are ready to be sustained. Especially in the prototyping phase, mutual learning is important. Accordingly, Peter Ramsden pleaded for the creation of networks and “a free movement of ideas” across Europe. Transparency is key to achieve the transfer of ideas: In order to spread a good idea it needs to be known. Open source is important to foster innovation – a precondition that is especially relevant in social economy running on public sector money.

Peter Ramsden led the audience through the different stages of creating and scaling innovation: After the idea creation in the prototyping phase, it is important to adopt a design thinking process and adjust an idea until it really works. If necessary, things have to be tried out 20 times before they are ready to be sustained. Especially in the prototyping phase, mutual learning is important. Accordingly, Peter Ramsden pleaded for the creation of networks and “a free movement of ideas” across Europe. Transparency is key to achieve the transfer of ideas: In order to spread a good idea it needs to be known. Open source is important to foster innovation – a precondition that is especially relevant in social economy running on public sector money.

He indicated that scaling can be hugely controversial as not every idea can be implemented at a larger scale. Sometimes spreading might be more appropriate. Systemic change might not be the answer to every question. Sometimes, gradual incrementalism might be the road to take. “Tweaking” or improving many small things at various points in the sense of the marginal gains theory can make the system a little bit better.

Tailored solutions

A point both Peter Ramsden and Aurelio Fernández López agree is that tailored, more personalised solutions are needed. Peter Ramsden emphasised the need to break the supplier market, which many labour market services are. The first step to innovate is to know what the clients need: Users are key sources of information to make innovation happen. Especially with groups far away from the labour market, however, it is not always easy to assess what their needs are. This is where innovators need to think like product designers developing tailored solutions adapted to local labour markets.

To illuminate how the rules of product design can be applied to service design Mr. Ramsden gave the example of the Copenhagen youth jobcenter. It was found that the jobcenter’s young customers disengaged from the services and repeatedly missed appointments. To understand why these young people were not satisfied with the services provided, the jobcenter engaged anthropologists who spent time with the young people and developed ideas how the jobcenter could become more welcoming. They found that the jobcenter was perceived as “unfriendly” with too much bureaucracy and that the language used was confusing to the young people. The result of the anthropologists’ findings was the introduction of a host welcoming the young people into the jobcenter and giving them directions and information on where to turn to, as well as information leaflets, posters and more visual “maps” guiding the people through the different services.

The Copenhagen jobcenter’s approach shows how innovation develops in a co-production process – which in this case means listening to the customers of services and tapping into the knowledge of the users of a specific service. Working with all stakeholders, services can be designed and delivered that meet users’ needs more effectively. However, such a co-production requires trust, which, in the case of the Copenhagen young unemployed, first needed to be established through a neutral third party, i.e. the anthropologists .

Innovative products in labour market services could include apps indicating new job openings or an app to cancel appointments. If people do not show up for job center appointments for whatever personal reasons they may have, time and resources are wasted (and job center customers usually be punished for this). If there were an app to cancel missed appointments, the job center customers’ situations could be better taken into consideration and freed capacities used more effectively.

Financing social innovation

After illuminating pre-conditions and different ways of social innovation, Peter Ramsden also gave a brief overview on ways of financing social innovation:

- micro finance, micro credit and peer-to-peer lending (e.g. Kiva): Kiva distributes money lent by private lenders to a particular cause promoted by people without access to banking institutions via microfinance institutions on five continents.

diaspora finance: The money migrants send back to development countries has become more important than overall development aid. - Alternative currencies – time banks, air miles, LETS local exchange trading systems, point money, internet money. Alternative currencies can also create social capital. Time banks, which can help people know each other and share different tasks, have proved to be very important in the context of health and care for the elderly. They can reactivate elderly people and contribute to foster active aging where people risk of becoming too passive. Alternative currencies, especially LETS schemes might also help those who have been away from the labour market in regaining confidence by contributing to local trade on a small scale.

- Impact investing and Social Impact Bonds: Impact investing describes socially responsible investment, in which the social gain is more important than the financial. The aim is the biggest possible societal benefit while ensuring asset preservation or even a moderate financial return. Social Impact Bonds (also known as “Pay For Success bonds”) are a public private financial instrument, in which bond holders (private investors) get a return – that is are paid back by the state – only if they achieve target social impacts. In such a multi-stakeholder approach, social service providers agree to achieve measurable social impact. The intervention is financed by private investment capital. If the desired impact is achieved, the private investors are paid back not by the social service provider but the state. As an example, Peter Ramsden referred to the Peterborough Prison Bond aimed to reduce recidivism of short term inmates which lies at 70%. Reduction needs to be by 7.5% p.a. over 5 years to achieve return.

- Crowd funding: On crowdfunding platforms like kickstarter money is collected through individual contributors who do not receive any returns but just want to support a certain project. Crowdfunding is usually seen as a new concept and has undoubtedly received a major boost through internet platforms like kickstart or indiego but, as Peter Ramsden pointed out, the concept is actually quite old: An early crowdfunding project is the Statue of Liberty: In 1884, the Americans had to build a pedestal to accommodate the gift of the French but initially couldn’t collect enough money for the construction. Only through a crowdfunding campaign gathering 100,000 dollars through micro donations of mostly less than a dollar could the Statue be finally installed. Peter Ramsden estimates the impact crowdfunding can have on the creative sector as very important. Regarding fighting social exclusion and poverty, however, he is “not convinced”.

- Challenges (e.g. Bloomberg challenge): In challenges ideas for solving local problems may be awarded. For creating apps for example hackathons have proved to be very efficient.

Summarising the new financial models, Mr. Ramsden called the innovation of financing social services a major area, where we are only at the edges. However, finance is also “where the dragons lie”: Many of the financing options are quite risky and often bring only mixed results as for example the EU scheme JESSICA.

Social Impact Bonds are currently seen as a silver bullet but might turn out to be a Faustian Pact as they are very complex and might lack transparency and accountability. Mr. Ramsden’s advice therefore is to test and pilot them first and to closely examine the results based on control groups.

For more on innovative financing of social innovation please refer to Mr. Ramsden paper for the OECD “Innovative Financing and Delivery Mechanisms for Getting the Unemployed into Work”: http://www.oecd.org/site/leedforumsite/publications/FPLD-handbook7.pdf

On SIBs in Germany: http://www.betterplace-lab.org/de/blog/erster-social-impact-bond-in-deutschland

Conclusion

Summing up his presentation, Peter Ramsden pointed out that for really achieving systemic change one has to:

- reframe the question

- move away from “end of the pipe” solutions and

- focus on results

Most approaches in the labour market are what Peter Ramsden refers to “end of the pipe solutions”: Instead of fixing the problem many labour market projects are just cleaning up the mess of problems that happened years earlier when someone didn’t get proper education in school, got into drugs or in short, when something in some person’s live went wrong that we haven’t been able to fix. This is what he means with “reframing the question”, i.e. getting away from solving “end of the pipe” problems and improving what gets into the pipe.

Mr. Ramsden pointed out that most of the examples mentioned so far are “tweaks”, little adjustments making the system a little bit better in the sense of the marginal gains idea that changing many small things in different places can have an impact.

However, he suggested that sometimes it is the system itself that has needs re-thinking. One way of doing this is to look at results but this is also where “the dragons lie”. One should acknowledge when the system is not working. For example is despite multiple interventions no progress is made as in the case of a family in Swinden: Mr. Ramsden showed a slide with a photo of a long wall with many post-its, each post-it representing a local authority or other public agency intervention with a single family over years. The cost of this family for the public purse is 250 000 EUR per year and despite all these interventions, the well-being of this family has now improved.

For Peter Ramsden, one solution lies in bringing together results and finance. As it is now, the financial system does not reward the people who actually make the change. In general, investment for social interventions (like the nursery provision or training schemes) comes from a local authority but the saving is accrued by the national governments. The problem then arises of how to make this finance circuit “virtuous”, i.e. rewarding the people who make the change happen, results and finance flowing together. This is where the above mentioned finance solutions come in. Social Investment Bonds are one way of doing this as they incentivize positive behavior. But the question, Mr. Ramsden raises at the end, is if the private sector loop is really needed or if a stronger focus on results might be enough. Therefore measurement, social experiments with randomised control groups, value for money and social returns on investment is key.

Finance, according to Mr. Ramsden, can be part of systemic change but “only if the other cogs are working as well”. He concluded his speech with a warning on technocratic solutionism. Some systems fail for the same reason banks have failed: The banking system worked for them, not for us, and also other systems are at risk of being run by vested interests.